Addiction is a robust, acquired need to use a psychoactive substance or perform an activity. A person with an addiction uses a substance or engages in behavior whose rewarding effects provide an irresistible incentive to repeat the activity, despite the harmful consequences. Addiction can include the use of substances such as alcohol, inhalants, opioids, cocaine, and nicotine, or behaviors such as gambling, shopping, playing computer games, eating, or having sex.

What does addiction look like?

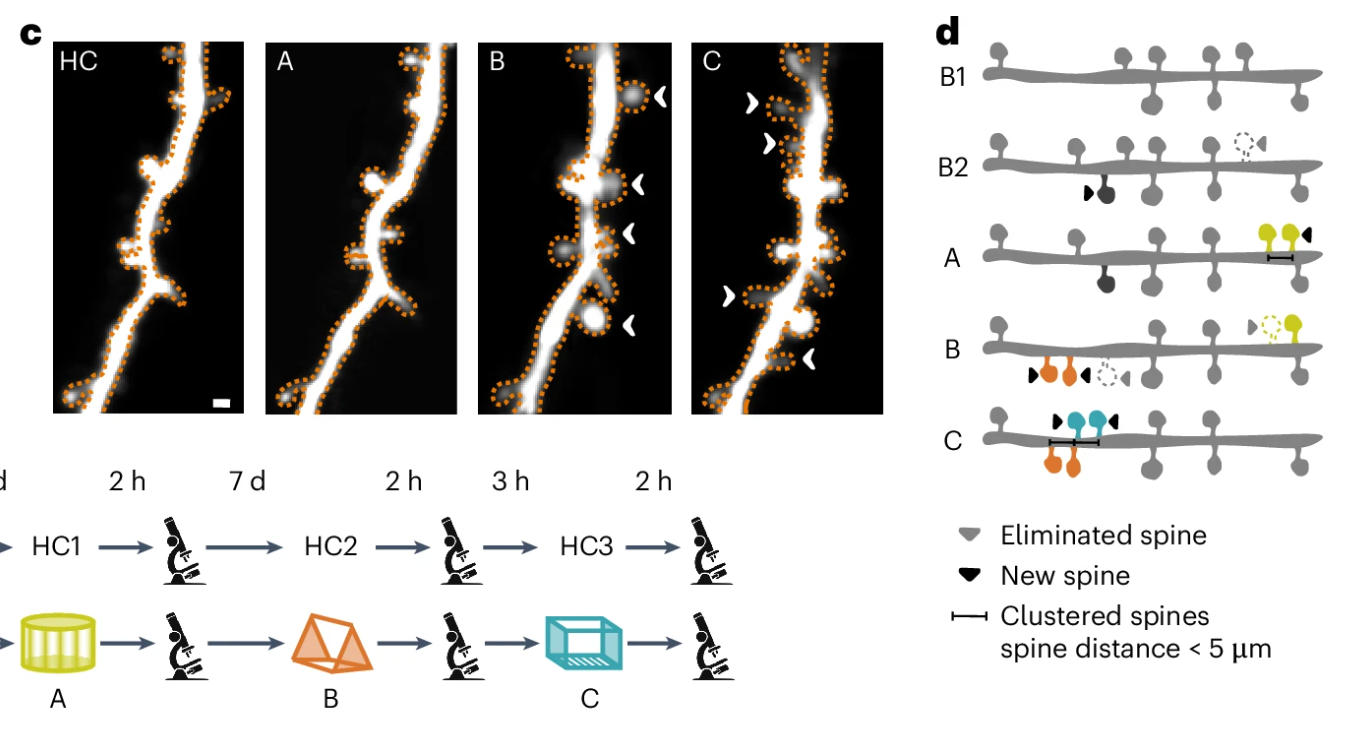

Substances and addictive behaviors share key neurobiological characteristics: they intensely engage the brain’s reward and reinforcement pathways, which include the neurotransmitter dopamine. They lead to the pruning of synapses in the prefrontal cortex, the seat of the brain’s highest functions so that attention is highly focused on signals associated with the target substance or activity.

A person experiencing addiction may be unable to stay away from the substance or stop the addictive behavior, show a lack of self-control, have an increased desire to consume the substance or perform the behavior, deny the presence of problems, be characterized by a lack of emotional reactivity or experience feelings of hopelessness, feelings of failure, guilt, and shame.

Because addiction affects the executive functions of the brain, people who develop an addiction may not realize that their behavior is causing problems for themselves and others. However, over time, addictions can seriously interfere with daily life. The road to recovery is rarely straightforward. People experiencing addiction are prone to cycles of relapse and remission. This means that they may go through phases between heavy and mild substance use or engaging in particular behaviors. Despite these cycles, addictions typically worsen over time. It can lead to lasting health complications and serious consequences, such as bankruptcy.

Addictions often co-occur with mental disorders. The individual may then use substances or behavior as maladaptive means of self-medication. This is especially the case with anxiety and depressive disorders, schizophrenia, and sleep disorders.

The most common causes of addiction

No substance or activity causes addiction on its own. Its development is most often influenced by a mosaic of complex cultural, social, and situational factors combined with psychological, biological, and even related to an individual’s characteristics.

There are many theories about the causes of addiction. Some emphasize the causal role of individual variations in genes that make a substance or experience more or less pleasurable. Many models of addiction emphasize the influence of individual psychological factors, whether personality factors, such as impulsivity or sensation-seeking, or psychopathology, such as the negative effects of early trauma. Other theories of addiction formation focus on the role played by social and economic factors, such as the strength of family and peer relationships and the lack of educational and vocational opportunities. Nevertheless, all models share a common theme – there is no single path that leads to addiction, and no single factor makes addiction inevitable. Addiction does not arise without contact with a given stimulus, but the stimulus is not the determining and prejudging factor in the development of addiction.

The main risk factors for the development of addiction include genetics, environment, and the individual’s predisposition.

Genetics

Genetics looks at how and why certain traits are passed on to children from parents. Genes can play a significant role in addiction – the greater the closer the genetic relationship between individuals. In other words, people with first-degree relatives (parents, children, siblings) who struggle with addiction are more likely to develop an addiction.

Some studies show that genes can account for up to 50 percent of a person’s risk of addiction, although the degree of genetic influence changes over time. Nevertheless, there is no single gene or even group of genes that lead to addiction.

Biological determinants

However, an individual’s biological conditioning is not just genes. For example, physiological responses are important, including the way the body metabolizes or breaks down and eliminates foreign substances such as drugs or alcohol, which is strongly dependent on the presence of different enzymes and can vary greatly between individuals and even between ethnic groups.

For example, studies show that the Japanese have unique variations of certain alcohol-metabolizing enzymes that are not found in other populations. Alcohol consumption quickly causes unpleasant discomfort, discouraging drinking. It follows that biological factors, such as enzyme profile, can affect the amount of alcohol consumed, the pleasure of the experience, the harmful effects on the body, and the development of addiction.

Environment

There are many factors that influence addiction beyond genes and biology. One of the most significant is the family environment and childhood experiences. Family interactions, parenting style and level of supervision all play a role in the development of coping skills and vulnerability to mental health problems.

A role in the development of addiction may be:

- Peer pressure – friends play an important role especially in the lives of teenagers. Peer behavior patterns influence everyone in the group.

- Unstable home environment (including parental separation or divorce).

- Drug use by parents and criminal activity by caregivers.

- Presence of drugs at home or school.

- Community attitudes and influences – if the community condones the consumption of substances or the display of the behaviors in question, this can influence whether a person will develop an addiction.

Childhood experiences, both positive and negative, can have a significant impact on a person’s physical and emotional health. Adverse childhood experiences are stressful, traumatic events that can lead to problems including substance use disorders. Examples of traumatic childhood experiences include:

- Physical violence.

- Sexual violence.

- Mental violence.

- Physical or emotional neglect.

- Being a witness to violence.

- Having a family member with a mental illness.

- Having a family member with criminal activity or incarceration.

- Having a family member with an addiction.

It is worth remembering that there are also protective factors that can minimize the risk of addiction. This includes, for example, children growing up with caregivers who provide good behavioral role models, situations where family members have positive relationships and a sense of community, there is a strong anti-drug policy at school, and individuals are able to develop self-control and self-discipline.

Mental health

There is a strong link between a person’s mental health and the development of substance use disorders. People may use drugs and alcohol to self-medicate or cope with problems. Individuals suffering from anxiety disorders, mood disorders such as depression or bipolar disorder, and those with antisocial personality disorder are more likely to develop substance use disorders.

Changes in the brain due to mental health disorders can affect or lead to substance use and vice versa, and affect how a person feels the effects of substances. Because of this, it is possible to fall into a dangerous and debilitating vicious cycle.

Treatment of mental disorders can reduce the likelihood of future drug use. Pharmacotherapy, family therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and group therapy are most commonly recommended.

Stress

Stress is a risk factor for many types of maladaptive behavior, one of which is the development of addiction. Difficult events in early life and cumulative negative experiences in adulthood – especially those that are unpredictable and emotionally intense – alter the reactivity of brain structures involved in learning skills, motivation management, stress control, and impulsivity, among other things, increasing vulnerability to addiction and risk of relapse.

Prolonged childhood stress disrupts adaptive coping and, through the overproduction of cortisol, is particularly damaging to the hippocampus, disrupting cognitive functions including memory and learning ability. Severe or persistent difficulties in early life alter the course of brain development and can permanently disrupt emotion regulation and cognitive development. Moreover, they affect the sensitization of the stress response system, so that it will overreact to minimal levels of threat. This makes individuals exposed to long-term stress more likely to feel overwhelmed by the normal difficulties of life. For this reason, chronic stress is also a cause of the development of anxiety or mood disorders.

Individual differences

Among the many factors that have been shown to influence the development of addiction are self-perception, emotional state, occupational status, stress reactivity and coping skills, perceived physical or emotional pain, personality traits, educational opportunities, important goals and progress toward them, and opportunities and access to rewarding stimuli in life.

Addiction and the brain

The brain plays a leading role in addiction as in all human behavior. The decision to try a stimulus is activated in the “executive” part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex. Ingesting a substance or performing an action provides a strong impulse to the nucleus accumbens, a cluster of nerve cells below the cerebral cortex, which responds quickly by releasing dopamine. This neurotransmitter is often referred to as the “pleasure molecule.” It’s the chemical underlying motivation, meaning its function is to focus attention and push people toward certain goals.

Because abused substances act directly on the brain’s reward center to deliver a high, which involves the rapid and intense release of dopamine, addiction can be seen as a shortcut to reward, which over time can lead to high mental and physical costs. The feeling of pleasure triggered by the increase in the neurotransmitter likely arose to encourage the repetition of behaviors that support individual and species survival – eating, interacting with others, having sex. However, the mechanism that once promoted survival may now be associated with unpleasant consequences.

Despite the threat, such intense gratification is a strong argument for re-taking a substance or repeating a behavior. Especially since the body becomes accustomed to the rapid ejections of dopamine right after a dangerous stimulus, reducing sensitivity and susceptibility to softer stimulation.

Repeated exposure to a rewarding stimulus changes brain structures in many ways. It stimulates the paraventricular nucleus – overactivity gradually weakens its connectivity with the prefrontal cortex, the seat of executive functions. One result is impaired judgment, decision-making and impulse control, the hallmarks of addiction.

Scientific research supports the idea that addiction is a habit that quickly and deeply takes root and is self-perpetuating, altering the brain’s periphery as it is aided and abetted by the power of dopamine. The brain prunes the neural pathways of attention and motivation to preferentially notice, focus, desire and seek the substance or behavior. What begins as a choice becomes, in a sense, a prison.

In summary, parts of the brain are involved in addiction such as:

- The nucleus accumbens, a cluster of cells below the cortex in the basal forebrain that triggers the need to pursue a goal. Sometimes called the brain’s “pleasure center,” it is a key element in the brain’s reward structures and releases dopamine in response to positive experiences and the anticipation of such stimuli.

- Dopaminergic neurons, which are concentrated in the paraventricular nucleus and when activated as a result of a positive experience, form connection pathways to other parts of the brain.

- The prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for such executive functions as judgment, decision-making, and impulse control; gradually weakens in response to excessive activation of reward structures by rewarding stimuli.

- The amygdala, which registers the emotional significance of perception, is highly sensitive to cues associated with reward stimuli and fuels the rise and fall of desire.

- The hippocampus, the seat of memory; under the influence of dopamine, the memory of anticipated reward causes excessive activation of reward and motivation structures and reduced activity in the cognitive control centers of the prefrontal cortex.

Unlike other organs, the brain is designed to change because its mission is to keep us alive, and to protect us, it must be able to detect and respond to the ever-changing dynamics of the world around us. The brain’s neuroplasticity, its ability to shape and reshape itself in response to the environment, enables humans to survive and thrive in many of life’s dynamic conditions. This also underlies addiction, as well as playing an important role in recovery.

Hunger always begins with a stimulus – it is triggered by some sight, sound, memory or sensation associated with a substance or behavior. The brain’s amygdala body recognizes the emotional significance of the stimulus. Then a wave of dopamine released in the goal-oriented hemispheric nucleus drives the search for the pleasure trigger.

Overcoming addiction usually involves not only stopping the use of a substance or the performance of a behavior, but also the discovery of meaningful activities and goals, the pursuit of which provides the brain with a reward trigger.

Prevention of addiction

Addiction is a serious but preventable and treatable condition. Early intervention and preventive measures can reduce the risk of addiction in children and adolescents.

The following methods can be helpful in reducing or preventing the onset of addiction:

- Increase education about the emergence of addictions and the effects of substances and behaviors on the body.

- Psychoeducation and learning how to adequately cope with problems such as stress.

- Presenting alternatives to dangerous behavior, such as leisure activities and hobbies.

- Access to addiction treatment and mental health services.

- Teaching impulse control, or the ability to manage desires and delay gratification.

- Monitoring children’s behavior, supporting their physical and emotional development, responding to their needs, setting limits and enforcing discipline.

- Developing a strong social support network.

In its simplest form, drug addiction can be seen as a way of “hacking the brain” – finding a shortcut to feeling psychologically rewarding by bypassing the usual activities that stimulate such feelings and directly manipulating the neurochemicals responsible for them.

Just as recovery from addiction requires focusing on rewarding activities other than drug use, so does prevention. The definition of a fulfilled and happy life varies from person to person, but psychology distinguishes several of its key factors – a sense of self-respect and self-esteem; meaningful interpersonal relationships that create a sense of belonging; opportunities for growth and development; work that is engaging and rewarding; opportunities to experience pleasure; and having hobbies.

Prevention strategies are less effective if a person has already developed an addiction. Individuals struggling with addiction may benefit from drug rehab programs that help reduce the consumption of a substance or the performance of an activity.